Brant Guillory, 25 March 2021

Warrior Knights is a board game of diplomacy, commerce, and, of course, warfare, in the Middle Ages. It is published by Fantasy Flight Games. The game covers a hypothetical kingdom in Europe, with real-world territories along the edge of the map, such as Ceylon, Alexandria, and Syracuse.

On #TBT, we bring you the occasional classic article – an older review or analysis piece we wanted to rescue

The knights and barons involved are also hypothetical, but have names evocative of the kingdoms of the Middle Ages: Baron Raoul d’Emerande is Spanish, Baron Mieczyslaw Niebieski is Polish (or perhaps Czech). In all, there are 6 Barons, each with 4 subordinate nobles. Although the names are aligned by nationality, there is no real attempt to have them reflect any real personalities from history.

The original Warrior Knights was designed by Derek Carver and published in the mid-1980s by GDW. The current version is described by Fantasy Flight Games as being reinvented for a new generation while paying homage to the original. It does not appear that Mr. Carver was involved in the design of the current incarnation.

click images to enlarge

PLOT & PRESENTATION

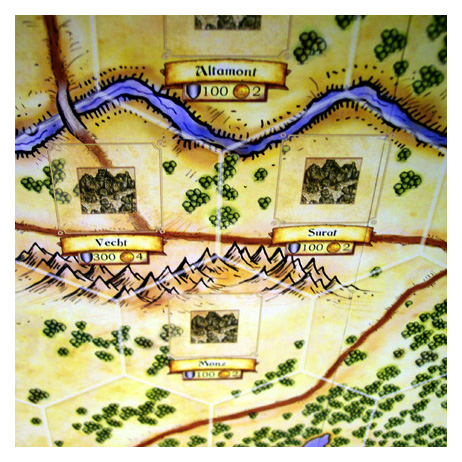

The King is dead! The Barons (represented by the players) are vying for control of the kingdom, and have sent their nobles forth to forcibly stake their claims to the throne. Although the trappings of the Middle Ages are all present – mercenary armies, siege warfare, heavy church influence in events, fortified cities – no attempt was made to tie this game to the succession in any real kingdom. In fact, the cities of the kingdom are an eclectic mix of names from many languages: Semlik, Vecht, Surat, Roczak, and Altamont are among the towns awaiting the players’ forces.

Each player controls one Baron, and the rules use the terms “player” and “Baron” interchangeably. Each Baron controls four nobles, who, in turn, control the Baron’s troops, both loyal regulars, and mercenaries.

Barons may become, through gameplay, either the Head of the Church, or the Chairman of the Assembly. These offices can have a considerable impact on the turn-to-turn play of the game, and are often contested on each turn. The Chairman of the Assembly determines many of the actions that happen in any given game turn; he also gets to wield a cool, and incredibly sturdy, gavel ‘counter’ that’s almost 4 inches long and (despite being cardboard) makes an incredibly satisfying rap on the table. The Head of the Church gets a similarly-hefty scepter, but doesn’t get to wave it around as often.

Barons may become, through gameplay, either the Head of the Church, or the Chairman of the Assembly. These offices can have a considerable impact on the turn-to-turn play of the game, and are often contested on each turn. The Chairman of the Assembly determines many of the actions that happen in any given game turn; he also gets to wield a cool, and incredibly sturdy, gavel ‘counter’ that’s almost 4 inches long and (despite being cardboard) makes an incredibly satisfying rap on the table. The Head of the Church gets a similarly-hefty scepter, but doesn’t get to wave it around as often.

Barons compete for influence within the Kingdom. The player with the most influence when the influence pool is exhausted becomes the King, unless a player manages to conquer half of the cities on the board first.

Although the game does not portray the succession of an actual kingdom, it is sufficiently flavored such that players will have little problem accepting the game’s premise of medieval diplomacy and warfare. The titles, commands, graphics, and agendas at the assembly are all obviously medieval-influenced, and create a fine atmosphere for gaming the era of knights, maidens, pennants, tournaments, and sieges.

Warrior Knights does not contain any elements of fantasy. Although there are some places where divine providence rears its head, it is through the Grace of God and His Church that anything supernatural takes place. Even then, there is no real need for much suspension of disbelief. Examples of events triggered through the “church” mechanics include a flood, arson, a broken family line, or good trade winds. There are no sorcerers hurling fireballs at the attackers from the city towers.

SET-UP, GRAPHICS, AND DOCUMENTATION

The game box is 11.5 inches square and almost 3 inches deep. The cover depicts a rather mean-looking, uh, warrior knight, in full plate armor and helmet, with a sword and a billowing red cape. This knight is a repeating motif that is found every side panel, as well as the back of the box. I’m not sure the box would stop a bullet, but it’s sturdy enough that it’d probably protect gamers from most thrown edged weapons.

Inside the box, there is a mounted, folding, four-panel map. Much like the box, the map is clearly meant to survive the Apocalypse. Four sheets of counters hold roughly 380 counters, plus the gavel and scepter. There is a large shrink-wrapped pack of cards holding about 300 of the little buggers. 24 plastic cities and 24 plastic nobles round out the box. There are no dice – because players won’t need them! The card-driven mechanics are explained below, but the Fate deck serves as the randomizer.

The map illustrates the hypothetical kingdom with a hexagonal grid. The hexes are almost three inches across, and of the 36 on the map, roughly half contain cities. There are also roads, a river, and several mountain ranges, all of which affect play. There are many hexes covered with forests, which do not. Each of the city illustrations are the same, and some cities have a port icon indicating that players may embark their nobles there.

Around the edge of the map are six additional overseas cities, as well as three “expedition tracks” to follow commercial ventures (see below). There are numerous places to lay out cards, because, hey, with 300 of them, they’ve got to go somewhere! There is also an area to store the influence pool from which players take their influence as they earn it. Finally, there is a track where Barons place their shields as they line up to hire mercenaries. There is no turn record around the map, nor are there any administrative references, such as turn sequence guides.

The hexes are large because there are times during gameplay when multiple nobles will occupy a hex with a city. The figures of the mounted nobles are not small, either; while they are roughly 1/72 scale, each is armed with a relatively impressive weapon (lance, axe, etc), adding to the physical space they take up. There are four different models, each with a different-shaped base. Each of the six colors has one of each figure, for a total of 24. Additionally, there are 24 small plastic city sculptures. The cities need to be small; when a player takes control of a city, an ownership counter is placed under it on the mapboard.

With over 380 counters, players can expect many different kinds of chits. Fantasy Flight Games are known for their voluminous numbers of counters littering the gameboard, and Warrior Knights is no different. Counters allow players to track their gold, votes, faith, influence, and casualties. Other counters are placed under cities to indicate ownership and/or fortification. Others are used to mark the locations of Baronial strongholds. Other counters track the number of breaches in each city’s defenses. Still others depict the coats-of-arms of each Baron, and are used to mark their places in line at the mercenary hiring hall, or to mark ownership of their monetary investments in an overseas expedition. The expeditions have counters of their own, too. And there’s the gavel and scepter, which are apparently considered ‘counters’ as well (according to the rulebook) but are almost props.

The counters are not greatly detailed, but are attractive and functional. Flags are used for influence, scrolls for votes, crosses for faith, and tombstones for casualties. They are also very dangerous projectile weapons, so hand them across the table, and never throw them, unless the recipient just backstabbed someone at the Assembly.

The cards are divided into four, uh, no five, uh, well, each player has their own… aw heck, there’s a lot of cards. There’s a deck for the Assembly, full of agenda items on which the barons vote. There’s a deck of mercenaries full of soldiers to be hired. There’s another deck of events that may be good, bad, or neutral, and may target one or more barons. One small set of cards are the neutral action cards (explained below). Each player has a small stack of cards that serve different purposes, since each player has his own action cards, as well as cards representing his nobles, troops, and baron/stronghold. And finally, the fate deck is the randomizer used to resolve all manner of mechanics throughout the game. Agenda cards contain text and a decorative border, while mercenary cards depict a wide variety of different soldiers entering battle. All of the mercenary cards of any given nationality (Tuscan, Lombards, Swiss, etc.) have the same illustration, whether they are in “denominations” of 50, 100, 150, or 200. Event and action cards also lean heavily toward text with decorative borders, while the cards depicting nobles and barons all have portraits. Each deck has its own distinctive background, allowing them to be more easily sorted into their 864 different piles.

The rulebook is a full-color, finely-illustrated, 20-page square demi-monster. Although well-written and full of examples, it occasionally takes some left-turns in its sequential presentation of gameplay, causing players to skip around quite a bit, especially the first time through. Instead of simply explaining the three main phases of each turn and then detailing special triggered events, the rulebook delves into the details of each special phase within the “action” phase of the turn. And while these special phases (described below) do actually happen in the action phase of the turn, they are not present in every turn, and an action phase could go by with none of the special phases being triggered. However, when first learning the game, players must read through each of the special phases before reading about the end-of-turn upkeep effects, which close out each turn.

The art design and presentation overall is very nice. It’s certainly nothing players will be embarrassed to show their friends, and there’s not much doubt where the retail price of the game went. Opening the box is like opening a treasure chest of components and laying it out on the table makes a grand visual impact. Laying them all out on the table also takes up a great deal of real estate. This game would be challenged to fit on a three-foot-square card table, and even then only with two-three players.

MECHANICS

Some games are easy to define as “area control” or “auction mechanic” or “movement and challenge”. Warrior Knights is not so easy to define. There is certainly combat, but even combat contains elements of bluffing with the card-resolution mechanics. Area control leads to increased resources for players, but is not necessarily the key to victory. Bluffing and deal-making are both prevalent in the Assembly. Resource management involves not simply tracking gold, and allocating it to get-rich-quick schemes overseas, but also managing votes, faith, and influence.

In short, there’s no one path to victory. Warrior Knights elegantly blends all of these into a game where planning is paramount, and yet still left to some whims of chance. With two different victory conditions (collect votes or conquer cities) players can choose the path they prefer to seize the crown.

In short, there’s no one path to victory. Warrior Knights elegantly blends all of these into a game where planning is paramount, and yet still left to some whims of chance.

Each player controls four nobles, who, in turn, command the Baron’s forces in the field. Soldiers are a mixture of loyal regular troops and mercenaries. Each noble also has his own special ability, such as dealing extra casualties in battle. In order to command nobles to take actions, players must use an action card. At the beginning of each turn, players pick out the six actions they wish to execute and sort them into three stacks of two each. Then, every players’ cards from their first stack are consolidated into one stack; their second stack of cards are then consolidated, as are their thirds. The Chairman of the Assembly adds to each of these stacks two of neutral action cards. Each of these three stacks are then shuffled by themselves, and executed in order.

So, a player knows that during the first action phase, he will execute his “Levy Taxes” action card, and his “Mobilize Forces” action card, which allows him to attack. What the player doesn’t know is exactly when they’ll be executed relative to the other players. If two players are poised to assault the same neutral city, it is up to the shuffling of the action cards to determine which one goes first. A player may find himself executing two actions back-to-back early in the phase, and then being forced to sit idly by while other players press their advantages before play moves to the next stack of event cards.

Players have some control over the order in which their own actions take place, however. Because the first stack is completely resolved before moving to the second, players can place their actions in stacks that allow them some sequencing of events. For instance, players may stack cards in the first stack allowing them increase their forces, before playing their cards in the second stack that allow them to attack.

Once players execute an action, that card frequently gets allocated to a stack tracking overall progress toward a special turn phase, either wages, assembly, or taxation. Once placed in one of these stacks, the card stays there until that phase is executed, potentially making that card unavailable for next turn’s actions. Once enough cards pile up in the assembly box, for instance, players go immediately to an assembly phase, where several agendas are voted on by the players. These agendas can have many different – and often immediate – effects on the turn. A baron may find himself elected the Lord Great Seneschal, an office which comes with an additional 150 troops. Another motion may ban all mercenaries of a certain nationality, which can immediately remove a good chunk of a baron’s forces from an impending battle.

Another special phase allows players to hire mercenaries, but at the same time also paying their current soldiers any wages due. The other special phase allows players to collect taxes based on their current holdings. Any of these special phases immediately interrupts whatever action deck is currently being resolved; it will be completed before further action cards are played.

Event cards may also trigger an expedition to the orient in search of riches. Barons may finance trips to China, Ceylon, or the Spice Islands. When the expedition reaches its destination, a card is drawn from the fate deck to see the outcome of the investment. Investors may recoup up to four times their investments, or may lose everything. These expeditions are tracked on the mapboard.

In all, players have a lot of irons in the fire on any one turn. They may need to cut a deal with a rival to get a motion pushed through at the Assembly. They may need to play action cards that garner votes in anticipation of a big motion, but at a cost of limiting their on-board options. They may want to invest in an expedition, but the stack of cards about to trigger a Wages sub-phase is getting pretty large, and the mercenaries don’t take IOUs.

Additionally, events in one turn will have significant impact on future turns. As action cards pile up waiting to trigger a special phase they are unavailable to players. Players will be faced with decisions such as whether they should give up a “Levy Taxes” card on the next turn in order to use it now, knowing it’ll likely sit on the board for at least one turn. Cards that allow nobles to move and fight in the same turn are then left on the board for a special phase. Cards that allow nobles to move or fight are returned to a player’s hand, prompting decisions as to whether a player should make a strong push this turn or wait. Or should I build more slowly and risk someone else’s action card coming up first, which may result in one player beating several others to a hotly-contested city?

Managing soldiers is also a challenge. Should I build up a strong force and hope the wages don’t come due any time soon? Or should I try to fight with several smaller forces and concentrate them on certain areas? Some players may be tempted to fight with a smaller (and therefore less costly) force, but nobles without soldiers assigned to them are kept off the board, and there are Assembly motions that permanently ban such “cowards” from returning to the game.

Certain action cards allow players to gain faith tokens for serving the church. The player with the most faith tokens holds the scepter as the Head of the Church. Whenever an event card is drawn, the Head of the Church assigns it to a recipient. Event cards with red backs are bad, those with green backs are good. The Head of the Church has the option to pay one faith to target another player with a red one; paying one faith also allow him to target himself with a green one. Once the event card is drawn, the players may then decide whether to pay any associated cost to prevent its effects. The rules specifically explain that players may examine the card and determine its effects on its targets before deciding whether or not to pay the cost to avoid it. Negotiations over who pays what part of the cost in support of which players are just another part of the game.

If this sounds convoluted and involved, it is – but only the first time through. Once players have completed one or two full turns, and at least one of each special phase, references to the rulebook drop off dramatically. The rhythm of the game is not difficult to pick up, and the players worry about turn-to-turn planning instead of ensuring the rules don’t bite them in the posterior.

The game is billed as one of “warfare” rather than “tactics” and the combat system truly supports this.

Combat is rather simple. The game is billed as one of “warfare” rather than “tactics” and the combat system truly supports this. Preparations for the battle are more important than execution, and a properly prepared commander will rarely lose, even with the randomness of the card resolution mechanic. First, a player must have an action card allowing the attack. Then the player must be able to get to the target of the attack. Some action cards allow a player to move and attack with the same card; others allow an attack only in the currently-occupied hex.

Each noble has a special ability, and three of the four abilities replicate combat effects from the cards in the fate deck. Players draw one card for each 100 soldiers in their army in combat, plus 2 cards for the commander’s tactical skill. Players examine their cards and discard two of them back to the fate deck. The cards are then revealed. Some cards deal 100 casualties; others prevent 100 casualties. Other cards add one tactical victory to the battle. To resolve the battle, begin by comparing casualty cards. If one side is killed, then the battle is over. If both sides have forces left on the field, then compare cards granting tactical victories. The player with most “+1 victory” cards takes the field.

The loser’s outcome depends on just how many victory cards the winner has. As always, bargaining (before the attack) is encouraged, if a player wishes to avoid the fight. Retreats may cause mercenaries to desert, and an inability to retreat may result in commanding nobles catching a bad case of the death.

Cities are attacked in much the same way, except that casualties are dealt to the city walls in the form of “breaches”. When the number of break tokens exceeds the a city’s defensive value, the city falls. The breaches remain, though, and must be repaired for the city to regain any defensive value.

Randomization is not done with dice, but rather with the Fate deck. These cards are drawn approximately every 10 seconds of the game. In fact, if players find themselves having played for at least five minutes without drawing a Fate card for something, they’ve likely missed something. Each Fate card has a Baron, a noble, a combat effect, a city, a mercenary nationality, and a revolt indicator, as well as the results of any trade expeditions. Any time the rules or game mechanics indicate that player should randomly “choose a noble,” for instance, he draws a Fate card. That card specifies which Baron’s nobles are targeted (by coat-of-arms), as well as which specific noble (by shape of the base of the figure). If a Fate card is drawn indicating one which is not in play (for instance, if only four players are in the game and the noble drawn is one of those not being used) simply draw the next card in the deck. In all, the Fate cards are a nifty mechanic that allows for random effects without a multitude of charts to cross-reference endless d6 rolls.

GAMEPLAY

With equal elements of Diplomacy and Risk, and a good deal of Medieval: Total War thrown in, Warrior Knights has something for everyone. A shrewd player can survive a game on his own, without cutting many deals. A shrewd player might also find himself at the mercy of a bad shuffle that gives an opponent an advantage in performing actions first.

One of the elements of a great game is that there is no one path to victory. Warrior Knights doesn’t just have multiple victory conditions, it has multiple ways to accomplish any of them. As players compete for influence, they may choose to do so through conquest, trade, voting, or trickery.

Setup can be time-consuming, with the multitude of counters needing to be sorted. Additionally, this game will take up most of a dining room table, especially with four or more players. Fitting more than four players around the board can be a challenge also, since there are only four sides to the board, and the “bank” of additional money, votes, and faith needs to be somewhere accessible. However, players are setting up one of the most attractive games on the market.

Play is so finely balanced that each player essentially starts with an identical set of resources. Every player has four nobles with the same special abilities. Each player starts with the same number of soldiers, gold, votes, etc. Each player has the same options available as action cards. While players do choose their starting locations on the map, and the starting locations of their nobles, each player is (un)constrained by the same guidelines. In short, there is nothing to distinguish the “British” baron as being particularly British, other than the name.

The greatest drawback of the game is that it is hard to play with only two or three players. A group of four to six allows for alliances, vote-trading, backstabbing, and all sorts of other political nastiness. However, gathering a group of four to six players with several hours to kill isn’t always feasible. The published playing time of two to four hours seems very low. A two-hour game would probably look like a group of experienced players mowed down by a buzzsaw Baron who had every card break in just the right fashion. A first-time group of four to five players can expect to spend three to four hours, minimum, to get through the first game. Crack a beer and pass the pretzels!

REPLAY VALUE & SOLITAIRE PLAY

This is not a game for solitaire play. In fact, it would difficult to really play well with only two people. As noted above, it is best played by a group of four to six.

However, replay value is fabulous. Since there are so many strategies worth pursuing, as well as a deep deck of agenda items for the Assembly phase, players could easily play 10 games without seeing two similar ones.

SUMMARY

Warrior Knights is a game of medieval warfare, not combat. The abstract resolution mechanics reward preparation over execution, and that may turn off some hard-core grognards. But going into the game with an understanding of what’s in store should temper expectations. However, the player that simply tries to steamroll the board with a mercenary horde may find himself hamstrung with adverse effects either through Assembly motions, or events thrown his way by the Head of the Church.

While not a greatly detailed game, Warrior Knights is a complex one. The mechanics are simple enough, but there are so many different resources to track and ways to use them that players are constantly re-evaluating their position in the game. Paying attention to the game between action cards is paramount; this is not a game to be played with a football game on in the background.

That said – it’s a blast. The political element allows players to deal, double-cross, and ally with each other without worrying about who has the biggest army on the board. The card-driven randomization of the game is everywhere, from the order in which turns are taken to the likelihood of a city revolting against its ruler. The balance is smooth and every player has a chance to win, with no inherent advantages or disadvantages built in based on nationality or background. But is it not so delicately balanced that one card can ruin the game. Every player starts with the same resources and the player who best manages them will usually win, regardless of random effects.

Warrior Knights is probably best-suited for a weekly game group looking for a game that can involve a larger number of players than a traditional wargame. Bloodthirsty players can attack at will, while more cunning ones can claw their way to the top. Warrior Knights easily accommodates all types.

Thank you for visiting The Armchair Dragoons and spending some time with the Regiment of Strategy Gaming.

You can find the regiment’s social media on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, and occasionally at a convention near you.

We also have our Patreon, where supporter can help us keep The Armchair Dragoons on the web, and on the podcast.

We welcome your feedback either in our discussion forum, or in the comment area below.